A Student Guide to Using Grammarly

Pro-tips for students deciding whether and how to use AI responsibly in their coursework

This page provides students with a concise guide to responsibly using Grammarly in their coursework at UIC. The guide below is organized according to the "stages" of writing, clarifying where the "lines" might be between acceptable and unacceptable use of Grammarly in each stage. The most important takeaway for students is that the safest bet will always be to check the syllabus and, if needed, ask the instructor what their expectations and policies are regarding generative AI use in coursework. The introductory section on "AI Policies" points to broad guidelines offered by UIC and the UI system. The concluding section addresses the "plagiarism" problem in a nutshell.

Our recommendation to students reading this guide is to start with these two sections, then dip into the sections covering the stages of writing as needed. An overview of the stages of writing is also provided in case it might be helpful.

If you're a student or faculty member and want to provide feedback on this page, contact our learning design specialist, James Sharpe.

Text Container

Introduction

What is Generative AI?

If you don’t feel confident in your basic understanding of generative AI, the University of Illinois system provides a quick but comprehensive overview of generative AI for students, faculty, and staff.

UIC has also released broad guidelines for adopting AI over the past few years, and various departments and organizations within UIC have released more granular recommendations, often tailored to their particular needs.

While all these recommendations are helpful, sometimes specific departments, programs, or even courses have their own policies concerning AI. The English department, for example, currently requires instructors teaching English 160 and 161 to include this policy language in their syllabuses:

“All submitted work must be created by you. Plagiarism is work that has been:

– Created by someone else.

– Created by AI (without the instructor’s permission).

– Created for another class and reused for this class.

– Paraphrased from someone else without credit to the original author.

– Quoted from someone else without credit to the original author.

Maintain your integrity when completing assignments and give credit where it is due. If you are ever unsure about what constitutes plagiarism, ask me. If you have plagiarized, you may be subject to disciplinary actions. These may include:

– Failing a particular assignment.

– Failing the entire course.

– I may also file an incident with the Office of the Dean of students.”

(First-Year Writing Program syllabus template)

In these courses, submitting any writing that was composed by generative AI without explicit permission from the instructor could be grounds for serious disciplinary consequences, depending on the situation. It’s imperative that you check with your instructor, syllabus, or a department liaison (office coordinator, department head, etc.) to clarify the limits of acceptable generative AI use for your particular context.

This is the most important recommendation LTS makes to students considering generative AI for coursework, so it’s worth repeating: You need permission to prompt, whether that comes from a syllabus, an instructor, or a program, department, or college-level policy.

Framework

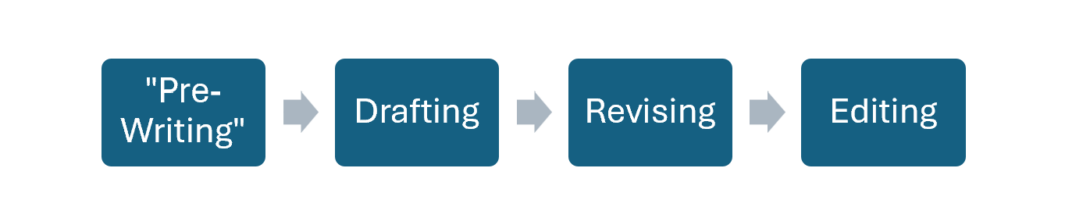

For simplicity’s sake, the writing process can be broken down into four broad “stages.” It’s important to note that this is just one way to picture the writing process, and many writers cycle through these stages or between them repeatedly and in a non-linear fashion. Nevertheless, these stages can help organize and clarify appropriate uses of Grammarly throughout the complex process of writing academic (and other) texts.

“Pre-Writing”

- Pre-Writing includes all those activities writers engage in before beginning an official “first draft.” The term is in quotations because many compositionists question whether it makes sense to suggest that these activities are somehow “not” writing (and thus “pre”-writing). We use it here heuristically to refer to all those activities we engage in that don’t seem like “writing” in the vernacular sense but that prepare the writer for that moment when they finally open a blank document and consciously begin a first draft.

Drafting

- Drafting describes the stage during which writers switch from note-taking or freewriting to composing standard paragraphs they intend to serve as the building blocks of their final product.

Revising

- Revising refers to a stage in the writing process during which writers consider large-scale changes to the text including, for example, re-arranging its parts, reframing its thesis, re-writing whole or highly significant portions, adjusting the style or voice of the entire project, and more.

Editing

- Editing typically refers to the last stage in the process during which writers make final small-scale changes such as correcting “sentence-level” errors, finalizing formatting (citations, line-spacing, graphs and tables, etc.), and adding or removing relatively small amounts of text as needed (words, clauses, or a sentence or two here and there).

Very few writers, if any, follow this linear model strictly, and these “stages” could just as well be construed as “modes” of writing. As an illustration: composition instructors often advise students to avoid “editing as you write” because it is an extremely common pattern in undergraduate writing but often interferes with students’ ability to engage with their material creatively and intuitively. Writers often switch rapidly between drafting and editing, even when that’s not always the most productive practice. Likewise, many writers move fluidly between drafting, revising, “pre-writing,” and drafting again.

Section 1

As a student, you’re already familiar with the kinds of activities sometimes referred to as “pre-writing.” Research, note-taking, mind-mapping, lists, and freewriting are all common examples. Grammarly can perform several pre-writing tasks with human-like results. Most basically, it can generate lists of potential paper topics and act as a kind of dialogue partner with the user to “talk through” questions in a way that could lead to useful insights for their project.

How do instructors feel about students using Grammarly for pre-writing? No comprehensive surveys have been done, but it’s important for you as a student to be aware of the most common perspectives.

Supportive: some instructors view AI-assisted pre-writing as a positive enhancement to students’ workflows and performance. These instructors would have no problem with you using Grammarly to suggest topics or work through ideas and questions as a precursor to drafting your paper or project. There is a growing consensus that the best practice in these cases is to disclose how you’ve used AI somewhere in your final project.

Skeptical: other instructors, however, view AI-assisted pre-writing as potentially undermining the formative effects of engaging in the pre-writing process without such assistance. As always, you need to check your syllabus or department policy to determine whether you can use Grammarly with AI. You need permission to prompt.

Section 2

There are, at the most basic level, two ways to use Grammarly during the “drafting” stage of the writing process.

- You can use Grammarly’s standard editing and proofing functions as you write.

- You can have Grammarly artificially generate draft material on your behalf in response to prompts, or by “extending” a sentence or paragraph you wrote yourself.

The first option is widely accepted as fair and responsible use of Grammarly across UIC’s colleges and departments. However, keep in mind that language programs may institute particularly strict policies about Grammarly. If the purpose of an assignment is to help the student acquire and practice grammatical competence in a new language, then the instructor may require students to complete such an assignment without any automated assistance.

The second option – using Grammarly’s AI to generate artificially composed text – is much more controversial, so it’s even more imperative that you check with your syllabus, instructor, or department before deciding to go through with it. The University of Illinois system has released general guidelines for students to consider while deciding how to responsibly and effectively integrate AI tools into their schoolwork. Again, as always, you need permission to prompt.

Section 3

As with the drafting stage, there are basically two ways to use Grammarly to revise a project. First, you can use Grammarly’s standard editing and proofing feature. Second, you can use Grammarly’s AI features to make medium- and large-scale changes to the text, typically by having it revise (by itself) whole sentences, multiple sentences, paragraphs, or more.

The first option is widely considered acceptable.

The second option can be an effective approach to revision so long as the student is aware of their course or program’s AI policies in particular and the general obligations they have to responsible disclosure and attribution.

Students’ obligation to disclosure and attribution is covered in the “drafting” section. Here, the important thing to recognize is that Grammarly uses generative AI in any operation that rewrites text the student has already written. If, for example, Grammarly offers you the option to “make this more persuasive” or “make this more informative,” in selecting such an option you are doing the same thing as typing a prompt into a generative AI – i.e. “Rewrite this sentence to be more persuasive: ‘…xyz…’” Whatever Grammarly composes, then, you must verify.

LTS strongly recommends that you experiment with Grammarly’s revision functions outside of coursework before using them on coursework. Consider these kinds of questions as you experiment:

- Is making a sentence “more persuasive” a task that can be scientifically defined and algorithmically programmed? If so, how? If not, what do you think Grammarly is doing when it “makes” your sentence “more persuasive?”

- How do you know when a change of phrasing has changed the idea being communicated? If you compare your original sentence to Grammarly’s revised sentence, can you explain what Grammarly’s changes accomplish rhetorically? Can you be sure that Grammarly’s revised sentence still communicates your idea, or is it possible that it has changed the idea as well?

Section 4

In this final stage of the writing process, Grammarly can be an effective tool (just like Microsoft’s spellcheck or “Editor”) for correcting “sentence-level” errors you may have missed throughout the process.

Minor grammatical mistakes, spelling errors, and matters of word choice are often the last set of corrections made to a text and, generally speaking, this is Grammarly’s best, most well-known, and most widely approved function.

Conclusion

There is a growing consensus among academic and professional organizations (for example, COPE, WAME, and JAMA) that the same principle applying to plagiarism, or at least a very similar one, also applies to AI-generated text: if the author did not write the text (or arrive at the idea) themselves, they have an ethical (and in many cases legal) obligation to attribute it to the proper source. In line with this principle, writers are obligated to “disclose” their use of AI somewhere in their text.

Of course, people often arrive at the same ideas independently of each other, and it would be impractical to require attribution of an idea to its absolutely “original” source. In practice, then, there is some flexibility and trust built into this principle. Professors and instructors have a responsibility to help students understand and effectively apply this principle, and students have a reciprocal responsibility to make good-faith efforts to apply it.

Compared to strictly human-written texts, the case of AI-generated text is simpler in one way and more complex in another.

It is simpler in the sense that the student using AI in the writing process is faced with a straightforward obligation: if they used AI at any point in the writing process, they have an obligation to disclose that information somewhere in or appended to the paper. Typically, this means identifying which AI was used, how it was used, and what, if any, text in the final product that was generated by AI.

It is more complicated, however, due to the opacity of generative AI’s composition process. It is already well-known that many generative AIs were trained on source data that was illegally or unethically acquired (see, for just one example, Meta’s case). When a generative AI composes a sentence, paragraph, or essay drawing on ideas and language from those sources, it may not be capable of attributing them correctly. When the student uses such text, they may find themselves in the difficult position of having inadvertently plagiarized. This is why the University of Illinois system AI guidelines for students, in alignment with widely acknowledged best practices, urges students to “Take full responsibility for generative AI contributions, ensuring the accuracy of facts and sources.”

In other words, when you use artificially generated text, it is your responsibility to verify that it is accurate and where it came from. As you decide whether and how to use AI tools in your coursework, keep in mind that this can be a remarkably time-consuming process.

And again, as always, you need permission to prompt.